Everybody knows (or should know) the story of sixteen year old Ramsey Campbell submitting stories set in Lovecraft Country to August Derleth. Derleth sent them back suggesting he set them in his native England instead of alien New England. Thus Campbell's Sevren Valley was born. Instead of Arkham there's Brichester, for Innsmouth there's Goatswood, and for Kingsport, Temphill.

The Chaosium published tribute to Campbell's Mythos fiction, Made in Goatswood has none of his early stories. I decided, in that case, I had better go and read them, first, for the fun of it, and then to get a better feel for what the collection authors' were hoping to emulate and memorialize. So, I'm also reading the latest edition of Campbell's first book, The Inhabitant of the Lake and Less Welcome Tenants.

The edition I have (2013, Drugstore Indian Press) includes an introduction by Campbell and his early correspondence with August Derleth. It's fun thinking of Derleth doing what Lovecraft did for him for Campbell. Derleth offered many suggestions that led to Campbell creating his own English setting and new deities for Mythos-inspired fiction. It's interesting to look at how Campbell turned out - one of the most important and revered horror writers - versus how Derleth did - a poor Mythos writer, but a solid editor.

If you haven't read Campbell's pastiches, they're clunky and more about monsters than atmosphere. Nonetheless, they are a bunch of fun. Some are only echoes of stories by HPL, but in others you can already sense his eventual predilection for grotty, urban unease forming.

The best thing about them, though, has to be the monsters. They're more intimate than HPL's critters, and what they do to their victims more personal. Where Cthulhu or Yog-Sothoth's kid just step on you, Gla'aki and Eihort gut you up close and you can feel your life seeping away, torturous moment by torturous moment. So, today, I give you monster pictures.

If you haven't read Campbell's pastiches, they're clunky and more about monsters than atmosphere. Nonetheless, they are a bunch of fun. Some are only echoes of stories by HPL, but in others you can already sense his eventual predilection for grotty, urban unease forming.

The best thing about them, though, has to be the monsters. They're more intimate than HPL's critters, and what they do to their victims more personal. Where Cthulhu or Yog-Sothoth's kid just step on you, Gla'aki and Eihort gut you up close and you can feel your life seeping away, torturous moment by torturous moment. So, today, I give you monster pictures.

Byatis: "It had but one eye like the Cyclops and had claws like unto a crab. He said also that it had a nose like the elephants...and great serpent-like growths which hung from its face like a beard in the fashion of some sea monster. .."from "The Room in the Castle"

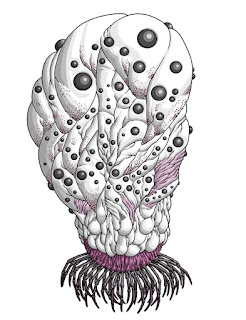

Gla'aki: "The centre of each picture was, it was obvious, the being know as Gla'aki. From an oval body protruded countless thin, pointed spines of multicolored metal' at the more rounded end of the oval a circular, thick-lipped mouth formed the centre of a spongy face, from which rose three yellow eyes on thin stalks. Around the underside of the body were many white pyramids, presumably used for locomotion. The diameter of the body must have been about ten feet at its least width."

from "The Inhabitant of the Lake"

Eihort: "Then came pale movement in the well, and something clambered up from the dark, a bloated blanched oval supported on myriad fleshless legs. Eyes formed in the gelatinous oval and stared at him."from "Before the Storm"

Y'golonac: "He saw why the shadow on the frosted pane yesterday had been headless, and he screamed. As the desk was thrust aside by the towering naked figure, on whose surface still hung rags of the tweed suit, Strutt’s last thought was an unbelieving conviction that this was happening because he had read thefrom "Cold Print"

Revelations…but before he could scream out his protest his breath was cut off, as the hands descended on his face and the wet red mouths opened in their palms."